Some Theory

Combined ideas on development of Hirschman (1945, 1958), Rosenstein-Rodan (1943) and Gerschenkron (1962) form one theory that accounts for industrialisation or its failure. The theory has been advanced further and formalised by Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny (1989a, 1989b), Krugman (1991a and b, 1992, 1994), and perhaps advanced in a different way by Lucas (1988, 1993, 2009).1 It basically centres on the role of increasing returns in industry as opposed to constant or diminishing returns in backward productive activities. The main Hirschman’s idea was the importance of forward and backward linkages, Rosenstein-Rodan’s on the role of fixed costs, and Gerschenkron’s about functional alternatives for coordination.

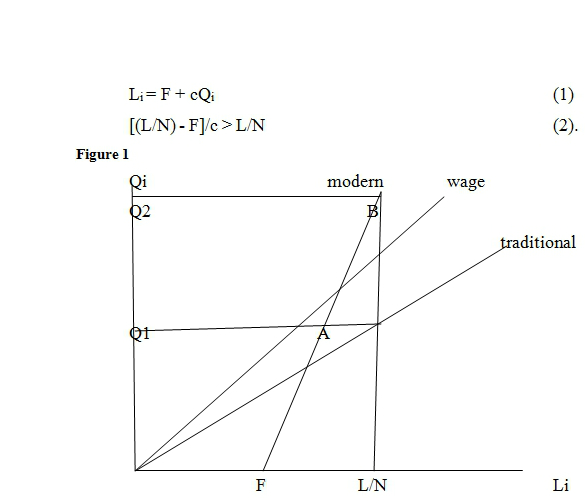

Krugman (1994) formalized these ideas with two simple equations and a figure that also captures the significance of multiple equilibria in development:

Here, L is labour, Li is the share of labour in the production of good i, N is the number of goods produced, Qi is the quantity of good i produced, c<1 is the marginal labour requirement in the modern sector, and F is the fixed cost. There is traditional (one additional unit of labour, one additional unit of product, c=1) technology and the modern (decreasing costs) technology with wages in the increasing returns industry being higher (w>1) than those in the backward constant returns sector (w=1). Clearly, point A is not where industrialisation happens (because it is loss-making), while it does at point B. Assuming wages in industry are the same as or higher (as in Figure 1) than in other sectors (e.g. agriculture, low productivity services), industrialisation will depend on the productivity of industry and the level of fixed costs. If fixed costs are high, it may not be profitable to industrialise. Also, if productivity is not much improved, investing in industry will not take place. So, the important factors are: wages, fixed costs, and productivity. Assuming that wages are influenced by the supply of labour and productivity is technologically determined, there is the issue of the investment in fixed costs left.

In a way, much of development economics is about investment in fixed costs and their recovery.

If one industrial firm is to enter the market, it may have to cover the fixed costs that may prove to be too high even with increased productivity. If, however, as in Hirschman, there are backward and forward linkages, it may become profitable for other industrial firms to enter as suppliers (backward linkage) or users of the original industrial firm’s production (forward linkage), then the industrial sector as a whole, including the pioneer industry, may become profitable.

Similarly, as argued by Rosenstein-Rodan, if there is coordinated investment in industry as a whole, than fixed costs will be more than covered by the higher productivity of the whole industry.

The investments in fixed costs may be undertaken by various economic agents, which is what Gerschenkron’s idea of functional substitutes is about: they could be undertaken by entrepreneurs, by banks, or by the state. The reliance on one or the other agent of investments explains both different approaches to industrialisation as well as different ways in which it can fail. In a sense, backwardness and its persistence are the consequence of the failures of these agents of industrialisation (lack of entrepreneurs, bank failures, or states not pursuing industrialisation). In the same way, the return to backwardness or the process of deindustrialisation is the consequence of the failures by entrepreneurs, banks, or states to invest in fixed costs and thus sustain or restart the process of industrialisation (for some history see Berand 1974, Berand and Ranki 1982, Palairet 1997).

Clearly, the presence of fixed costs, and by implication of increasing returns, leads to the possibility of multiple equilibria (production levels Q1 and Q2). Much of the research in industrialisation or development in general is about the ways to move from the backward to industrialised equilibrium (Hoff and Stiglitz 2001), of the ways of getting out of development traps (Azariadis and Stachurski 2005). Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny (1989b) discuss the Big Push, i.e. the coordinated investments in e.g. infrastructure which makes investments in industry as well as in infrastructure itself profitable. Krugman discusses the role that agglomeration plays in industrialisation (and also differentiates centre from periphery), while Lucas concentrates on the role of human capital and on the ways in which trade with more developed countries supports the process of learning by doing (Arrow 1962).

Most of these discussions concentrate on the role of the firms and on the state, though the role of banks has been strongly emphasized by Gerschenkron and by Schumpeter and his followers. In Gerschenkron’s theory of backwardness, industrialisation is triggered and sustained either by entrepreneurs that proceed to invest in a piecemeal manner or by banks or states that spur industrialisation by large scale investments in projects that lower the entrance, i.e. fixed, costs for industries. These are functional alternatives: there is not one path to industrialisation. In a way, fixed costs may be covered in a decentralised manner or in a more or less centralised way of coordination. In the latter case, industrialisation can proceed by leaps and bounds; indeed, the more backward the country is, the faster the catching up process. A backward country can jump immediately to the technological frontier if it manages to make industrialisation profitable by large scale investments in infrastructure and other fixed costs, e.g. in education.

So, the speed of industrialisation is determined by the degree of backwardness and the amount of investment in fixed costs.

Significant part of development studies is devoted to these (i) market led industrialisations (e.g. Sachs and Warner 1995), and to (ii) the theories of the big push. The former look into the role played by foreign trade and investment, and by the increasing returns that come with learning by doing, while the latter look at bank- and state-led investments. Also, failures to industrialise are explained either by the lack of market incentives, e.g. due to comprehensive protectionist trade policies or because of extractive domestic institutions (as in Acemoglu and Robinson 2006, 2012), or by bank and state failures. Gerschenkron (1962 and 1977) described a number of spurts that failed due to financial or policy failures (e.g. the cases of Bulgaria and Austria).

So, the persistence of backwardness can be explained either by market failures that are not being corrected for or by the lack of adequate agents of development due to either institutional or to policy failures. In policy terms, there are two different approaches in development economics: those that emphasize market led industrialisations and those that argue for the role of more interventionist industrial policies.

Transition and Deindustrialisation

In the case of transition from statist to market economies, there have been successes and there have been failures to industrialise. The Balkan region provides for a number of examples of failed industrialisations. There, industrial production has been substituted by constant return to scale services. In Central European transitions, initial recessions have been followed by significant industrialisation. In some other transition countries as well as the developing countries in the South Mediterranean, a failure to industrialise can be observed. So, in these groups of countries, there are all the important cases of successes and failures so that comparative analysis could prove useful.

What are the characteristics of the process of deindustrialisation? In the context of Figure 1, clearly there is an increase in fixed costs or a decrease in the productivity gap (e.g. by technological and human capital degradation of the existing industry) or a persistence of uncompetitive wages.

Thus, for one or all of these reasons, the economy moves from industrial production to less productive services.

The increased productivity gap with the technological frontier (perhaps the Gerschenkron’s advantage of backwardness) is supportive of industrialisation, while the increase of fixed costs (that indicates how big the push needs to be) may prove to be a major barrier. Change of wages is ambiguous because their decline in inherited industries means lack of demand for these industrial products, but perhaps also lower wage premium needed to move labour from services to more technologically advanced industry; by contrast, higher wages in industry may prove to present a barrier to investing in industry. In addition, there is a change in the composition of human capital which may prove more difficult to correct for through learning by doing. It may not be the level, but the educational structure that stands in the way of industrialisation.

The key factor that led to the bifurcation of the industrial development in some Central European countries and in those in the Balkans is the post-socialist transitional recession and different policies for adjustment that were chosen. Transitional recession has been described, but probably not convincingly explained. Early explanations that emphasise inadequate or timid liberalisation (Murphy, Shleifer and Vishny 1992) as well as those that rely on the emergence of large market and government failure, i.e. massive failure of coordination (Blanchard 1997, Blanchard and Kremer 1998) are not altogether persuasive. Theories of optimal unemployment in transition and those of credit squeeze and lack of sufficient demand do not account for different structures that emerged from transitional recession. Policy mistakes as in Krugman (1987) with similar arguments in Rodrik (2008) that affect dynamic comparative advantages are more promising, though they beg the question of why these particular policies, e.g. of overvalued exchange rate, are chosen?

In any case, the key role played by the transitional recession both fore reindustrialisation and deindustrialisation seems clear as does the differentiated policy response across countries in transition.

One issue that is particularly interesting is that of the losses in human capital that are due to deindustrialisation. Theories like those advanced by Lucas (1988, 1993, 2009) can explain the social process of human capital accumulation, but in the case of deindustrialisation there is the process of learning by doing through which knowledge is actually lost. For instance, it can be argued that MENA countries are not industrialised because of the slow process of knowledge acquisition. But they are at their technological frontier given their level of knowledge and the existing social conditions for learning by doing. So, there is no gap between the level of development and the accumulated human capital.

However, deindustrialisation is characterised by the move away from the technological frontier. This does not mean that there is no learning by doing going on but that it is such that it accompanies the move from a more productive industrial sector to the less productive services sector. The social process of transmission and acquisition of knowledge – learning by doing – is the same, only it moves the level of knowledge away from the previous technological frontier and of course even further away from that of the more advanced countries.

One way to address the understanding of this process is by analogy with loss of human capital that often occurs in migration. It may be dynamically comparatively advantages for a skilled worker to take up a less skilled job due to changing comparative advantages. Similarly, it may prove comparatively advantages to move away from industrial production due to changed comparative advantages. That less skilled job would have to learned too, so loss of human capital through learning-by-doing.

Industrial Policies

Given the importance of increasing returns, externalities, and thus imperfect competition in industrialisation, there is a prima facie case for policy interventions. Those come in two types: policies that support interdependencies and coordination and industrial policies properly so called.

Rosenstein-Rodan’s idea of coordinated investments in an underdeveloped region, i.e. group of countries like Central and Southeast Europe, follows on the Allyn Young’s (1928) discussion of increasing returns and economic progress which in turn is to a large extent an elaboration of the claim by Adam Smith that “the division of labour is limited by the extent of the market”. This suggests a role that liberalisation of trade across borders could play.

The growth of trade and the role of trade policy in industrialisation in general has been one of the most studied issues in development economics. Lucas (especially in 1993) has applied this idea to the process of learning by doing, i.e. to increasing returns to transfer of knowledge that trade brings about. This is a substitute for foreign investments, which have had more ambiguous effects both on industrialisation and on growth (see Lucas 1990). So, Lucas reformulated the neoclassical model of development that mostly relied on the productivity gap to that of industrialisation that mostly relies on the accumulation of skills and transfer of knowledge through learning by doing, e.g. through trade. That is like a decline in fixed costs that compensates for higher wages that need to be paid for industrialisation to get started.

Most other suggestions for policies for development attempt to identify an intervention that would push a country from backward to industrialising equilibrium. Krugman discusses mostly the process that would reinforce Hirschman’s backward and forward linkages, which could be initiated by a random shock, e.g. an entrepreneurial innovation or policy intervention. Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny suggest a big push of investments in fixed costs in order to internalise intra-industry external effects; symmetrically, deindustrialisation would be in part the consequence of these external effects that cannot be captured due to various coordination failures. Gerschenkron saw significant role for the banks and in case those were not supporting investments in industry, state could play a modernising role.

So, a larger market could solve the demand problem; trade could facilitate the acquisition of knowledge and thus technological advancement; banks could finance large scale investments; states could not only invest in fixed costs, including knowledge acquisition, but supply other institutional and policy prerequisites for industrialisation. By contrast, all these modernizing agents may fail and backward equilibrium may prove persistent.

These are mostly macroeconomic policies because industrialisation, and especially latecomers’ industrialisation, has been seen as a process that has to start with some kind of a big push. The reason has been that sufficient demand and sufficient interdependence is needed for the process to start and be sustainable. However, more often than not, industrial policies will be seen as microeconomic policy interventions (Acemoglu 2010). These are often called policies of picking the winners and are often blamed for rather unfavourable record of episodes where industrial policies have been used as an instrument of development. The objection is not so much that a diagnostic (to use Rodrik’s terminology) cannot be designed that would prove successful at picking the winner, but that this piecemeal approach, if that is what it is, may fail due to lack of sufficient complementarities especially in the home market as well as due to deficient domestic demand for industrial products.

An open economy should be helpful in that respect, but then the problem may be that there is no significant domestic spill-over due to the fact that all the forward and backward linkages are across the borders rather than domestically. Thus, the process of agglomeration, as argued by Krugman, may lead to lack of inter- and intra-regional convergence. In this context, various policies of building clusters have been suggested, though they are often difficult to devise and implement.

When it comes to policies and industrial policies in particular, there are at least two problems. One is that there are fewer instruments than targets and the second is that particular targets need to be chosen that have a more general impact. The first problem is to choose the better of the plurality of available instruments. It is similar to Simon’s problem of finding out the causal chain in the interdependent system. Though all instruments can be substituted one for the other, not all are as effective as the others. In a way, the symmetry between the instruments needs to be broken down somehow and e.g. subsidies need to be chosen over tariffs or tax system should be chosen over the exchange rate manipulation. Rodrik argues that globalisation has severely narrowed down policy choices so that basically only various types of subsidies or preferential treatment of local industries is left available. He solves the problem of the effectiveness of this instrument by arguing that only second-best instruments are left available anyway and those cannot be easily ranked by overall effectiveness.

The other issue is that of choosing the target of intervention. As the problem is to kick off the activity that will have most effects on the chain of interdependencies, Rodrik suggests that the shadow price of a policy intervention should be calculated (i.e. to calculate the Lagrange multipliers and rank them by magnitude) and then choose the one with the most “bang for the buck”. It is like choosing to build a highway rather than a number of local roads. So, it is not choosing the winners but kicking off the process of industrialisation, which once started has an almost sure, i.e. unconditional chance of succeeding (Rodrik 2013). Of course, in the case of persistent backwardness or in that of deindustrialisation, the interest is in the cases where those policies were either not attempted or have in fact failed.

Research Topics and Comparative Method

In the context of the simple model of development taken over from Krugman, appropriate polices that target (i) productivity, (ii) fixed costs, (iii) wages, and (iv) employment need to be designed. Those should address the key actors: firms, banks, and states. In the context of the theory of development, agents of development, i.e. firms, banks, and states could be looked at and compared across countries and regions. Firm development, trade, and learning by doing is one area of research. Financial controls or integration, i.e. the role of banks and financial markets would be another. Institutions and policies, e.g. investments in fixed costs, various protectionist measures, and interference with the prices mechanism could be the third.

For instance:

– How are larger firms established (so that intra-firm increasing returns can be captured)?

– How are banks induced to invest in large enough projects (so that industry wide externalities can be captured)?

– How are states steered to invest in fixed costs (so that there are economy-wide increasing returns to scale) and

– How to pursue macroeconomic policies that support industrialisation?

– By contrast, what are the structures of production, of finance and of policies that support deindustrialisation or stand in the way of industrialisation?

It makes sense to compare countries that have industrialised successfully, e.g. those in Central Europe, plus perhaps Turkey, with those that have de-industrialised, e.g. in the Balkans, and both of them with those that have persistently been failing to industrialise, e.g. in the MENA region. Comparisons could be cross-country ones or could rely on comprehensive country studies to capture both the patterns of industrialisation or of the barriers to industrialise and also the idiosyncratic element present in every successful and unsuccessful industrialisation. Also, having three groups of countries could allow a variety of methodologies that can identify causality to be employed.

References

Acemoglu, D., J. Robinson (2006), “Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective”, American Political Science Review 100: 115-131.

Acemoglu, D. (2010), “Theory, General Equilibrium, and Political Economy in Development Economics”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24: 17-32.

Acemoglu, D., J. Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail? Crown Business.

Arrow, K. (1962), “The Economic Implications of Learning by Doing”, Review of Economic Studies 29: 155-173.

Azariadis, C., J. Stachurski (2005), “Poverty Trap” in Ph. Aghion, S. N. Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth Vol. 1, Part A: 295–384. Elsevier.

Berand, T. I. (1974), Economic Development in East-Central Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Columbia University Press.

Berand, T. I., G. Ranki (1982), European Periphery and Industrialization 1780-1914. Cambridge University Press.

Blanchard, O. (1997), The Economics of Post-Communist Transition. Clarendon Press.

Blanchard, O., M. Kremer (1997), “Disorganization“, Quarterly journal of Economics 112: 1091-1126.

DeLong, J., L. Summers (1991), “Equipment Investment and Economic Growth”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 445-502.

Gallup, J., J. Sachs, A. Mellinger (1999), “Geography and Economic Development”, International Regional Science Review 22: 179-232.

Gerschenkron, A. (1962), Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Gerschenkron, A. (1977), An Economic Spurt that Failed: Four Lectures in Austrian History. Princeton University Press.

Hausmann, R., D. Rodrik, A. Velasco (2008), “Growth Diagnostics.” in J. Stiglitz, N. Serra (eds.), The Washington Consensus Reconsidered: Towards a New Global Governance. Oxford University Press.

Hirschman, A. (1945), National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. University of California Press (expanded edition 1980).

Hirschman, A. (1958), The Strategy of Economic Development. Yale University Press.

Hoff, K. (2001), “Beyond Rosenstein-Rodan: The Modern Theory of Coordination Problems in Development”, Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 2000, 145-176.

Hoff, K., J. Stiglitz (2001), “Modern Economic Theory and Development” in G. Meier, J. Stiglitz (eds.), Frontiers of Development Economics: The Future in Perspective. The International Bank for Research and Development, 389-459.

Krugman, P. (1987), “The Narrow Moving Band, The Dutch Disease, and the Competitive Consequences of Mrs. Thatcher”, Journal of Development Economics 27: 41-55.

Krugman, P. (1991a), “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography”, Journal of Political Economy 99: 483-499.

Krugman, P. (1991b), “History versus Expectations”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 651-667.

Krugman, P. (1994), “The Fall and Rise of Development Economics” in Lloyd Rodwin, Donald Alan Schön (eds.), Rethinking the Development Experience: Essays Provoked by the Work of Albert Hirschman, 39-58. The Brookings Institution.

Krugman, P. (1995), Development, Geography, and Economic Theory. The MIT Press.

Krugman, P. (1999), “The Role of Geography in Development”, International Regional Science Review 22:141-161.

Lucas, R. (1988), “On the Mechanics of Economic Development”, Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3-42.

Lucas, R. (1990), “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries?” American Economic Review 80: 92–96.

Lucas, R. (1993), “Making a Miracle”, Econometrica 61: 251-272.

Lucas, R. (2008), “Ideas and Growth”, Economica 76: 1-19.

Murphy, K., A. Shleifer, R. Vishny (1989), “Industrialization and the Big Push”, Journal of Political Economy 97: 1003-1036.

Murphy, K., A. Shleifer, R. Vishny (1989), “Income distribution, Market Size, and Industrialization”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 104: 538-564.

Murphy, K., A. Shleifer, R. Vishny (1992), “The Transition to a Market Economy: Pitfalls of Partial Reform”, Quarterly journal of Economics 107: 889-906.

Ostrom, E. (1990), Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Palairet, M. (1997), The Balkan Economies c.1800-1914: Evolution without Development. Cambridge University Press.

Rodrik, D. (2008), “The Real Exchange Rate and Economic Growth”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall: 365-412.

Rodrik, D. (2010), “Growth after the Crisis,” in M. Spence, D. Leipziger (eds.), Globalization and Growth: Implications for a Post-Crisis World. Commission on Growth and Development.

Rodrik, D. (2012), “Unconditional Convergence in Manufacturing”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128: 165-204.

Romer, P. (1986), “Increasing Returns and Long Run Growth”, Journal of Political Economy 94: 1002-1037.

Rosenstein-Rodan, P. (1943), “Problems of Industrialisation of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe” The Economic Journal 53: 202-211.

Sachs, J., A. Warner (1995), “Economic Reform and the Process of Global Integration,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1-118.

Young, A. (1928), “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress”, The Economic Journal 38: 527-542.

Peščanik.net, 05.05.2013.

________________

- One could probably add Romer (1986) and the endogenous growth theory. Also, Rodrik’s ideas on growth diagnostics and industrial policy (Hausmann, Rodrik, Velasco 2008, Rodrik 2010) could be fitted into this tradition, though he prefers to emphasise his debt to Karl Polanyi.

- Biografija

- Latest Posts

Latest posts by Vladimir Gligorov (see all)

- Kosmopolitizam je rešenje - 21/11/2022

- Oproštaj od Vladimira Gligorova - 10/11/2022

- Vladimir Gligorov, liberalni i nepristrasni posmatrač Balkana - 03/11/2022