OBSERVATIONS FROM SERBIA’S MEMORY LAB

Where does a contemporary history of Serbia begin? How is the Yugoslav legacy reflected within it? And does all the talk about memory and forgetting in post-conflict societies really help to answer these questions?

With such doubts I left Serbia this October. For the past six years, I have participated in excursions about memory culture across the post-Yugoslav region. Most of the study trips were organized by Memory Lab. This is a network of individuals interested in the culture of dealing with the past in Western Europe and the Western Balkans. Since our first meeting in Sarajevo in 2010, forty memory activists and analysts have travelled together to explore how the societies in Western Europe and the western Balkans perform their history. We have visited Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, France, Germany and the German-Polish borderland, Kosovo and Macedonia, Belgium; and in 2016, our joint study trip has leaded us to Serbia.

Every year, these five days in autumn as part of the Memory Lab were an intense experience for me. But exploring Serbia’s topics, forms and issues in representing its past was different. It was different for me as exploring Serbia’s memory culture was akin to mapping a vacuum. What does this mean?

On the first day, we traditionally hear lectures about the historical and social context of the country we are visiting. In Belgrade, one of the three female presenters came from the Institute for recent history of Serbia. She introduced the “Contemporary history of Serbia, with a focus on the period from WW2 until today”.

Our presenter began by referring to where we were geographically, namely, at the confluence of two rivers, the Sava and the Danube. And she sketched how those rivers were the borders of two competing empires and cultural spheres, the Austro-Hungarians and the Ottomans. Like that she marked the point of departure for the “Contemporary history of Serbia” as a location of cultural confluence. By choosing rivers as metaphors for a society’s history, our presenter also alluded to fluidity. In this manner, change becomes a crucial feature of history.

The first historical date which the historian mentioned was the foundation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1918 (at that time still the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes). After the first Yugoslavia, our presenter comprehensively elaborated on the particularities of Tito’s socialist Yugoslavia (social property, self-management, and non-aligned-movement). Finally, she concluded with stating: “Although all post-Yugoslav societies have their specificities, we can still discern many similarities”.

A speaking void of history

I am unable to recollect whether the historian used the word “Serbia” at all in her presentation. She presented contemporary Serbian history as a void. Neither did she mention the overthrow of socialist president Slobodan Milosevic in October 2000, nor the assassination of the democratic prime minister Zoran Djindjic in March 2003. Alternatively, she could also have started with 2003, the year when a democratic state named Serbia was proclaimed, albeit still in union with Montenegro. Yet neither this, nor the referendum for the separation of Montenegro from Serbia in 2006, or Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008 (perhaps the least surprising as Serbia does not recognize it) played any role in this historian’s “Contemporary history of Serbia”. Therefore, I was wondering: what does it mean when a professional historian presents their country’s contemporary history by avoiding conventional historical markers?

In this manner, the contemporary history of Serbia has become the elephant in the room.

Certainly, our presenter was aware that she was talking to Bosnians, Croats, Serbs, Macedonians, Kosovars and some western Europeans. Perhaps her presentation would have been different before an audience that was not predominantly from former Yugoslavia. Perhaps our presenter hoped that talking about socialist Yugoslavia was the safest ground in order to omit a discussion about the wars of the 1990s.

Then came the Q&A session. Somebody asked her about the recent rehabilitation of the Serbian WW2 general, Draza Mihailovic. During WW2, Mihailovic had lead Serbian nationalist fighters, commonly known as “Chetniks”. They initially fought against the German occupiers, but soon also attacked Tito’s partisans and the non-Serbian population in order to establish a “homogenous Serbia”.1 After the war, Mihailovic was tried for treason and war crimes, found guilty and executed under Tito’s rule. In May 2015, the Supreme court of Belgrade annulled the judgement from 1946 by stating that the trial did not follow fair procedures, but was ideologically biased.

During the controversial trial which did not so much tackle whether Mihailovic had committed crimes, but whether he had been afforded due process of law, many historians were consulted. A colleague of our presenter from the Institute of recent history had supported this symbolically important rehabilitation. Our presenter explained: “You can find all kinds of historians confirming all kinds of truths in this country.” My thoughts were: Everything means nothing. If every historian can claim anything, history loses its purpose to offer orientation in time. If everything can be history, the effect is disorientation.

Disoriented was I after this introductory session to the contemporary history of Serbia. However, the good news is that the elephant in the room as a speaking void only evolves out of something. That something around the void was here: socialist Yugoslavia and the nationalist Chetnik movement during WW2. It seemed to me that both historical references today function antagonistically: Tito’s Yugoslavia stands for a very specific socialism, for anti-nationalism and anti-fascism; whereas the Chetnik movement symbolizes a royalist greater Serbia, nationalism and collaborating with fascists.

Perhaps a contemporary history of Serbia becomes a mission impossible when it consists of constructing a meaningful story from two antipodes.

Souvenirs in Belgrade’s pedestrian zone:

a peasant, a statesman, a general – Serbia, Tito, Draza Mihailovic © Jacqueline Nießer

The awkward continuity of ‘the Yugoslavian’

But to be honest: I felt that all those –isms are more or less irrelevant. My impression was that what counts when praising the Chetnik movement is that it can clearly be identified as SERBIAN. This clear distinction of ‘the Serbian’ is crucial given the awkward continuity of ‘the Yugoslavian’.

Consider that the break with Yugoslavia in Serbia was not a deliberate one; Serbia never claimed independence from Yugoslavia. On the contrary, Milosevic promoted Yugoslavia in order to – in the rhetoric of our time – ‘make Serbia great again’. Remember also that Yugoslavia not only disintegrated through war, but through democracy as well. First there were elections, and then there was war. Eventually, the last state construct bearing the name ‘Yugoslavia’ vanished silently by constitutional change: in February 2003 the ‘Federal Republic of Yugoslavia’ became the ‘State Union of Serbia and Montenegro’.

Out of voting and fighting and transforming, Serbia remained as a kind of involuntary Yugoslav leftover after everybody else had created their own little, independent states. The scholar Nenad Dimitrijevic concluded in the year of Milosevic’s overthrow: “Serbian national identity no longer exists. The project that was aimed at the homogenization of all Serbs into the Great One (Serbia) led to the total destruction of the nation.”2

However, a country named Serbia exists. “Serbia has always remained somehow unfinished”, says the historian Dubravka Stojanovic. A destroyed nation in an unfinished state performs its history in voids. This sounds logical. But if you are a citizen of Serbia, this conclusion is a disaster.

Being Serbian

With Memory Lab we do not only visit memorials and museums but likewise reflect on what such experiences impart upon us. As memory activists and analysts we all are participant observers. The method of participant observation includes reflecting on one’s own position in the field. We are both the lab rats and the scientists of the Memory Lab all-in-one.

So, sometimes we discuss matters in small groups. In Belgrade, our task was to describe how we relate to Serbia. One Serbian participant from a human rights’ NGO explained: “I want to describe why I am disconnected with Serbia. I don’t relate to Serbia because I don’t identify with the official nationalist narrative.” Another stated: “I worked a lot on myself to be a Serb.” The researcher of the Pedagogy faculty saw a problem in constructing one’s identity through negation. She found arguments that made her feel comfortable saying “I am Serbian”. By belonging, she takes responsibility to transform what it means to be Serbian the way she wants it. Moreover, the pedagogue fears that by negating her Serbian identity because of dominating nationalist voices, she would neglect that there are many Serbs that do not fit this stereotype. Hence, disconnecting with her Serbian identity would re-inforce the division, whereas she strives to overcome such antagonisms.

A school teacher of language and literature in Serbia remarked: “Before the war, I was Yugoslav. Now I refuse to identify with a state or a nation.” That’s why she doesn’t define her subject of teaching more precisely than ‘language and literature’ (not ‘Serbian’, so that she can teach literature from across post-Yugoslavia). An LGBT+ activist stated: “I don’t usually say it, but I’m Serbian. My family is from Kosovo. When I told my mother that I’m trans-gender, she didn’t understand. Then, I explained to her: I was born a girl, but I do not identify with being a girl. It’s like being born a Serb, but I do not identify myself as Serbian.” The activist wanted to show how much identity is also a choice, or how identity is about acknowledging a certain ascription or not. To her surprise, her mother accepted her not identifying as a girl, whereas rejecting being Serbian was a point of contention.

In this discussion, however, I sensed that for all the participants the problem was not being Serbian. The problem was that being Serbian seems to require a singular response. Stojanovic describes this monism or anti-pluralism as a major problem of Serbian society. Nevertheless, the historian concedes that anti-pluralism is one of the few continuities that nurtures Serbian identity.3

This reflects a crucial dilemma: identity is about constructing continuity.4 But what if there are more ruptures than continuity to draw upon in your past? What if the place you live in has been the pawn of others for extended periods of time? The amplitude of ruptures and changes in Serbia’s past might explain the power of the anti-pluralist argument as well as the attraction of straight narratives that can be identified as “truly Serbian”.

But understanding where an argument comes from does not equate to its justification. If we perceive identity as a constructed continuity, then there is room for choice, like the discussion in our group illustrated. And when there is room for choice, then there is also room for change. However, it seems that many in Serbia have had enough of change in the last decades. Consider how war, hyperinflation and economic sanctions have shaken Serbia economically and politically.5

Nevertheless, I would like to imagine it differently at least: Wouldn’t the alternative be a pluralistic Serbia? And here, it is important to stress that the alternative would not be re-inventing Yugoslavia. I believe that pluralism should not be equated with the bygone multi-nationalism of Tito’s Yugoslavia.

Whereas I acknowledge that referring to the “Yugoslav experience”6 certainly triggers sympathy, particularly among the generations that have witnessed Yugoslavia, I believe that equating pluralism with Yugoslavia is a trap. I am afraid that suggesting Yugoslavism as a form of civic discontent against nationalism just reinforces the described paralyzing antagonism.7

Branding anti-nationalism, anti-fascism and anti-capitalism with “Yugoslavia” updates an ideological battle that has already been fought (and lost on both sides).

The ‘real’ Other

In order to exit the trap of this perpetuating historical antagonism, it might help to consider that another crucial part of identity construction is defining the self vis-a-vis the other. In this context, the manner in which Serbia constructs the ‘other’ gains in importance. With Memory Lab, we visited the Museum of Yugoslav history.8 Built in Yugoslav times as a gift by the town of Belgrade to Tito on the occasion of his 70th birthday on May 25th 1962, this complex included several museums and some residential buildings. After the leader’s death in 1980, a memorial center called the House of flowers was established as part of the museum. This is where Josip Broz Tito and his wife Jovanka are buried, and today it functions as a modern shrine.

Since 2013, Serbia supports the Museum of Yugoslav history as a cultural institution of national significance.9 This recent development, in my assessment, reflects a way out of the trap of historical antagonism; by acknowledging that the “Yugoslav experience” is part of Serbian identity. This means that Yugoslavia does not function as the Other, but as part of the Serbian self.

So, if the Yugoslav experience becomes an important component of Serbian identity, how is the other defined? When the curator of the Museum of Yugoslav history told us that 80% of its visitors are international, I imagined French, American, Polish and Russian tourists searching for the non-existent permanent exhibition about Yugoslav history. I also contemplated who would buy the Yugo-nostalgic T-shirts, bags and pencils in the museum shop. But then I recalled that once I almost missed a bus by lining up under “domestic traffic” when buying a ticket from Zagreb to Belgrade. The journey from Zagreb to Belgrade for me was not an international connection. This memory helped me to realize that 80% of international visitors mean that only 20% of visitors to the Museum of Yugoslav history are from Serbia. 80% come from outside Serbia, but it remains open whether they are from somewhere else in the world, or perhaps rather from the former Yugoslavia. Does this mean that the countries of post-Yugoslavia constitute a part of the Other against which Serbia defines itself?

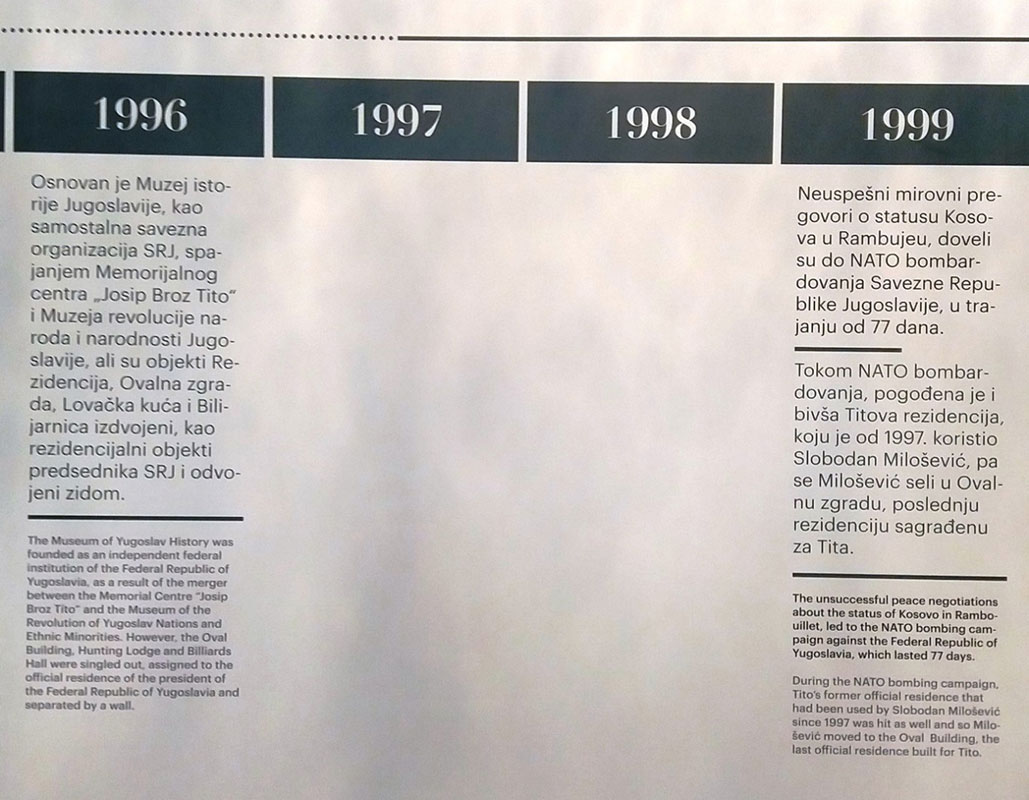

Perhaps analyzing another speaking void helps to answer this question. I mentioned above that the Museum of Yugoslav history is still developing its permanent exhibition. However, it displays thematic exhibitions, such as one in the House of flowers concerning the Tito cult. It included a timeline which illustrated my observation of contemporary history as a void.

The years 1997 and 1998 are represented here with a blank spot. No information is displayed in the timeline about the events of 1997 and 1998. For the year 1999, “unsuccessful peace negotiations over the status of Kosovo” are mentioned as a reason for the NATO bombardment of the then Federal Republic of Yugoslavia for two and a half months.

A war or a conflict in Kosovo is not mentioned at all. Consequently, for the visitor, the “peace negotiations” over Kosovo seem to evolve out of the blue – or rather out of the void. The mutual apartheid of Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo and the escalation of the situation in 1997 and 1998 through attacks by the Serbian police and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) seem to be, again, non-authorized knowledge. Therefore, no information is displayed in a timeline describing the most important facts of contemporary history in a public museum of Serbia.

Kosovo offers a good example as to how the post-Yugoslav countries are part of ‘the other’ against which Serbia defines itself. However, in contrast to the other post-Yugoslav countries, Kosovo officially still belongs to the Serbian self. I thought that this uncanny relationship is therefore expressed silently in a speaking void.

Forget memory, rethink history

Thinking in terms of memory and forgetting in post-conflict societies did not greatly assist me with my observations in Serbia. Perceiving history as an ambiguous process of knowledge production instead10 nurtured my investigation of the speaking voids of history as sites of silent knowledge. My approach might be compared to Jelena Obradovic-Wochnik’s exploration of silence as an integral element of dealing with the past.11 Whereas investigating silencing refers to the act of articulating or not articulating something, investigating voids explores the results of this articulation and non-articulation. The French anthropologist Roger Bastide concluded „when a structure survives, omitting particular elements creates perceptible ‘holes’, ‘gaps’, negative and real traces. So in some cases, we know about an item without knowing what it is – given that it is firmly embedded in a network of relationships.”12

In the case of Serbia, I see the Yugoslav legacy to constitute a prevailing network of relationships. That means contemporary Serbian history is embedded in Yugoslav history, which sounds more than obvious. Yet sometimes, even the obvious needs to be acknowledged.

Bibliography

Algazi, Gadi, Forget Memory: Some Critical Remarks on Memory, Forgetting and History, in: Sebastian Scholz/Gerald Schwedler/Kai-Michael Sprenger (Hrsg.), Damnatio in memoria. Deformation und Gegenkonstruktionen in der Geschichte, Köln [u.a.] 2014, pp. 25-34.

Calic, Marie-Janine, Geschichte Jugoslawiens im 20. Jahrhundert, München, 2010.

Halbwachs, Maurice/Coser, Lewis A., On collective memory, Chicago, 1992.

Jansen, Stef, Antinacionalizam: Etnografija otpora u Beogradu i Zagrebu, Beograd, 2005.

Mikus, Marek, ‘European Serbia’ and its ‘civil’ discontents: beyond liberal narratives of modernisation, in: Centre for Southeast European Studies (June 2013).

Obradovic-Wochnik, Jelena, The ‘Silent Dilemma’ of Transitional Justice: Silencing and Coming to Terms with the Past in Serbia, in: International Journal of Transitional Justice (2013), pp. 328-347.

Pescanik, Jugoslavenstvo poslije svega, http://pescanik.net/jugoslavenstvo-poslije-svega/, 09.12.2016.

Petrovic, Tanja, Towards an affective history of Yugoslavia, in: Filozofia i drustvo (2016), pp. 504-520.

Spaskovska, Ljubica, The Yugoslav chronotope: Histories, memories and the future of Yugoslav studies, in: Florian Bieber/Armina Galijaš/Rory Archer (Hrsg.), Debating the end of Yugoslavia, Farnham 2014, pp. 241-253.

Erinnerungskulturen: Erinnerung und Geschichtspolitik im östlichen und südöstlichen Europa, 16.12.2016.

Peščanik.net, 06.02.2017.

________________

- Marie-Janine Calic, Geschichte Jugoslawiens im 20. Jahrhundert, München, 2010, p. 160-161.

- Dimitrijevic, Nenad, 2000, “Proslost, odgovornost, buducnost” [“The past, responsibility, and the future”], Reč no. 57, March, pp. 5-16, here p. 16, translation by Dejan Ilic, in: The Yugoslav truth and reconciliation commission, Overcoming cognitive blocks. In: Eurozine, 23.4.2004.

- Pescanik, Jugoslavenstvo poslije svega.

- Maurice Halbwachs/Lewis A. Coser, On collective memory, Chicago, 1992.

- Marek Mikus, ‘European Serbia’ and its ‘civil’ discontents: beyond liberal narratives of modernisation, in: Centre for Southeast European Studies (June 2013) 7, here p. 23-24.

- Ljubica Spaskovska, The Yugoslav chronotope: Histories, memories and the future of Yugoslav studies, in: Florian Bieber/Armina Galijas/Rory Archer (eds.), Debating the end of Yugoslavia, Farnham 2014, pp. 241-253, p. 244.

- Stef Jansen, Antinacionalizam: Etnografija otpora u Beogradu i Zagrebu, Bgd, 2005.

- http://www.mij.rs/poseta/kompleks.html

- http://www.mij.rs/upoznajte/mij.html

- Tanja Petrović, Towards an Affective History of Yugoslavia, in: Filozofia i Drustvo XXVII (2016) 3, pp. 504-520, here p. 518.

- Jelena Obradovic-Wochnik, The ‘silent dilemma’ of transitional justice: Silencing and coming to terms with the past in Serbia, in: International Journal of Transitional Justice 7 (2013) 2, pp. 328-347.

- Roger Bastide, Les Religions Africaines au Brésil: Vers une sociologie des interpénétrations de civilisations (Paris: P.U.F., 1960), quoted by Gadi Algazi, Forget memory: Some critical remarks on memory, forgetting and history, in: Sebastian Scholz/Gerald Schwedler/Kai-Michael Sprenger (eds.), Damnatio in memoria. Deformation und Gegenkonstruktionen in der Geschichte, Köln [u.a.] 2014, pp. 25-34, here p. 32.