A country which changes and adjusts to new circumstances as slowly as Serbia has its major problems that are changing in an equally slow pace. In this case, problems consist of a stagnant economy and a fast increase in debt. These problems remain, even though they are at times suppressed by others. The IMF delegation’s mid-June visit to Serbia has briefly suppressed the country’s traditional problems, bringing to the forefront an additional one, namely the reform of the public sector. This problem is closely tied with the two aforementioned, fundamental ones. The IMF visit took place during an apparent deterioration of relations between Serbia and the West which could influence all three abovementioned issues.

Importance of the Arrangement with the IMF

With regard to Serbia and her fundamental problems, it is very important for the country to be given a positive assessment by the IMF during this review of the ongoing three-year stand-by arrangement of a total value of €1.2 billion. In case of a negative assessment, the arrangement with the IMF would be terminated, which would negatively influence not only economic growth, but also the country’s debt situation. If the support from the IMF would cease, the important issue would not be the loss of the aforesaid €1.2 billion – an amount which was not scheduled to be used by Serbia, but was supposed to be a reserve – a much greater problem would be the fact that borrowing at financial markets would become significantly costlier for Serbia, meaning that the debt service would be more expensive, and the risk of state bankruptcy would sharply increase. It is impossible to estimate in advance the magnitude of the deterioration (cost increase), as it depends on the creditors’ perception of the risk that a given country will not be able to repay the loan. Even without bankruptcy, increase of the debt cost would imply a necessity of a quick €1 billion decrease of state expenditures in several areas, which could primarily affect key budget items, such as new pension and salary cuts, less public procurement and lower capital investment. The decrease of state expenditure would influence a drop in economic activity in the country, meaning a drop in GDP and income. All this goes to show the close links between the outcome of the talks with the IMF and the other two main economic problems of Serbia.

Budgetary balance

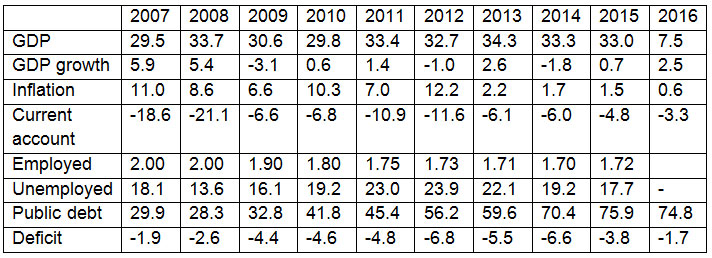

Given the importance of the outcome of the talks with the IMF, perhaps it is advisable to first examine Serbia’s hand while entering them. The cards have been shuffled, some are good, and some less so. The situation is not as bad when it comes to Serbia’s most important trump card in the negotiations – namely, the budgetary balance. After years of significantly high budget deficit, in 2015 Serbia has managed to lower it to 3.8%, following 2014 when it was as high as 6.6%. (see Table 1). During previous reviews, the IMF has positively assessed the state of the budget in 2015, and nothing has changed this time around, although Serbia’s deficit was one of the highest in Europe in 2015, as well. The issue which mattered to the IMF was the fact that the deficit was significantly lower compared with the previous year (2014) and that it was lower than it had been planned for 2015, by around 2pp (percentage points).

During the first few months of 2016, the budgetary balance in Serbia kept improving. This has occurred due to the increased economic activity in the year’s first half, slightly higher tax revenue and continued selective austerity (pensions, salaries). During the January-April 2016 period, the deficit amounted to around 25 billion dinars which is half of what had been planned for this period (50 billion). A deficit of 164 billion dinars or around 4% of the GDP had been planned for the entire year of 2016.1 Some unforeseen revenues (12.8 billion for the 4G network licensing) and unpaid severance (since there were no planned surplus dismissals from the public sector) have contributed to a better budgetary situation than expected during the first few months of 2016. Of course, one should bear in mind the fact that the deficit in Serbia could be at a very low level throughout the year and then dramatically increase in the course of only one month, as was the case in 2015. It was then that the deficit suddenly jumped as a result of a highly uneven distribution of state expenditure and delayed payments, mainly of guarantees and public enterprises’ expenditures.

The IMF had reasons to be content with both the economic growth and improved budgetary balance, but it was not in the focus of international creditors’ attention. Three other topic occupied the center of the negotiations: firstly, the question of the remaining state firms’ status, i.e. ending of the privatization process. Secondly, rationalization and dismissal of employee surplus in the public sector. Thirdly, the problem of non-performing loans.

As opposed to the budgetary balance, Serbia has a rather bad hand when it comes to all three abovementioned issues. Let us first examine the ending of the privatization, followed by the problem of surplus employees in the public sector and, finally, the state of non-performing loans.

Privatization

In 2015, the Government has made a promise to both the IMF and the domestic public that it would resolve the issue of the remaining state-owned enterprises – around 550 companies with over 80,000 employees. This is a major challenge for any government as the vast majority of these enterprises have no economic future having long lost their markets and are faced with huge accumulated losses; these are firms which, during the hitherto privatization process, either no one wanted to buy or were privatized but their privatization was annulled. Even though the total number of employees in those enterprises accounts for only 4% of the total number of employed persons in Serbia, the importance of this “sector” is greater, due to other, often non-economic elements. Some of the enterprises on that list employ many workers, some have numerous exterior partners, and others are significant for certain parts of Serbia and their development.

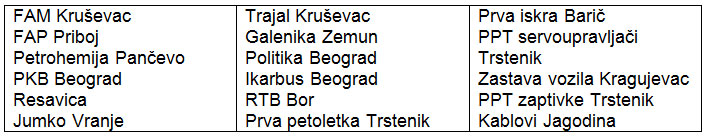

Already at the very beginning of the privatization procedure concerning these enterprises, public attention has focused on a very small number of them belonging on an otherwise rather long list. This was caused by a May 2015 Government decision to exclude 17 enterprises declared by the Government as “strategic” from the privatization procedure“. (see Frame)

Frame 1: Subjects of privatization of strategic importance

Source: Decision by the Government of Serbia, May 29 2015.

The Government has decided to protect those 17 enterprises from creditors’ payment claims until late May 2016. This period has expired, and in the meantime the problem of only 6 enterprises on the list has been resolved. Five enterprises went bankrupt (Prva iskra Baric, PPT servoupravljaci Trstenik, Zastava vozila Kragujevac, PPT zaptivke Trstenik, Prva petoletka Trstenik), whereas a reorganization program has been prepared for FAM Krusevac (the so-called Pre-Packaged Reorganization Plan). Smederevo Steelworks was not on this list of 17 enterprises; its assets were sold to the Chinese HBIS company for € 46 million, in April 2016. Srbijagas, Zeleznice Srbije, EPS are missing from the list, as well.

That is why the list of 17 “strategic” companies is only the tip of the iceberg called “public sector economy“ which becomes apparent if one looks at the “big picture”. Out of the total of around 550 enterprises, the procedure of liquidation, merger or privatization has been concluded in the case of some 300 companies employing 25,000 workers. What about the remaining 250 companies (minus the 17 “strategic” ones) with as many as 55,000 employees? Their status remains unresolved, the difference only being in the camouflage modalities – merger with other companies, postponement, association with the arbitration process within the framework of succession, etc. Therefore, the problem concerning enterprises in the public sector is of a much greater scope and gravity than it might appear upon first glance, particularly if one only focuses on the 17 protected ones.

If all remaining 11 out of the 17 “strategic” firms would continue to be owned by state, with no change whatsoever in their operation, it would cost the state at least €200 million annually. In other words, their continued operation would cost the same amount that is saved up annually through salary and pension cuts. There are several problems regarding these companies, as well as the entire remaining sector of publicly owned enterprises, which render the resolution of their status neither easy nor simple. Firstly, these enterprises “employ” around 21,000 persons directly, and an additional number indirectly (external partners). Their closure would increase the unemployment rate which is high as it is. Secondly, entire regions are dependent on some of those enterprises, such as RTB Bor, FAP or Resavica. Thirdly, interest groups in those firms are powerful, with a highly profiled self-management syndrome. Opposition political parties could only further enhance their protests. Fourthly, a part of the electorate would be dissatisfied with the closure of some of those companies, as they had been important economic factors for decades. Many voters believe that they are still important, failing to realize that it would be better for them to close down, as they have long lost their market and today operate with losses covered by taxpayers.

Even though we did not learn much about the content of the discussions between the IMF and the Government of Serbia, apart from vague press releases, it is quite certain that the remaining state enterprises have been one of the three main topics of negotiations. This is understandable, since those companies are a burden to the budget, create no income and pollute the economic environment by spreading insolvency and other bad business habits around them.

Surplus of employees in the public sector

The surplus of employees in the public sector represented the second fundamental topic of negotiations between the IMF and the Government of Serbia. With some 1.2 million employees in the private sector and around 750,000 employees in the public sector, along with 1.7 million pensioners, Serbia has exactly twice as many supported persons than the total number of employees in the private sector. It is as if Germany had 8.3 million employees in the public sector and 13.5 million in the private sector. Germany, however, has 43.4 million employees, around 7 million of which are in the public sector, the rest in the private one. It is as if in Serbia, out of the 1.95 million persons currently employed, around 300,000 would be in the public sector, and the remaining 1.65 million in the private sector. In other words, public sector in Serbia should account for less than a half, and private sector for more than a third in order for the situation to be comparable with the German one. Germany is perhaps not the best role model as it has a large public sector. One could bring up other comparisons but the message is clear. The public sector in Serbia is oversized and too costly. With regard to this, the IMF has a rational demand, namely for the public sector to be at least slightly decreased. However, that will be even more difficult to accomplish than the privatization of state-owned enterprises, as is evident by what has been done until now.

The Government made a promise to the IMF that it would decrease the number of state employees in 2015 by around 14,500. Although Government circles claimed that the number had been diminished by around 9,500, it is more likely that the cut amounted to around 5,000 which is the result of the so-called natural decrease (retirement, death, relocation). It has even been reported2 that the promise made to the IMF had been fulfilled – namely, that there are 8,511 less persons employed at the level of republic organs, 250 at the level of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina and 5,751 less employees at the local level, which amounts to 14,512. However, the timeframe referred to was not specified, nor was the source of this data cited. Even more interestingly, the budget shows no record of such huge severance payments.

Simultaneously with the pressure to decrease the number of employees in the public sector, a contrary process is taking place – employment through party and friendly channels. Naturally, there is no statistical evidence to document this, but everyone who lives in Serbia is familiar with such examples from direct experience or through the media, hence one can conclude that employment through party connections is a rather widespread occurrence.

Layoffs in the public sector represent a highly delicate task for any government and it is always met with strong resistance. It is unclear how it will transpire, what kind of dynamic it will have and to what extent it will be misused. The details of the agreement with the IMF on this issue also remain unknown, except for the framework number of a 15,000 decrease in 2016. The dismissal dynamic will be possible to be monitored directly by means of reports and, indirectly, by means of severance payments.

Non-performing loans

Non-performing loans (NPL) have emerged as the third main topic of negotiations with the IMF. The topic had not been announced in advance, but its importance certainly deems it worthy of attention. It is not to be excluded that the bank lobby in Serbia has influenced the IMF mission to include this issue into the negotiation agenda. Non-performing loans in Serbia account for around 22% of the total loans, more than in Croatia (17%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (14%) or Slovenia (10%), and other European countries. Bad loans are the result of political influence exerted on banks, as well as a bad loan policy of the banks themselves. In absolute figures, bad loans in Serbia are estimated at around €3.5 billion, which is more than the ten-year profits of all banks in Serbia combined. The NPL problem will probably be opened and dealt with once similar issues are initiated in Europe. The fact that Serbia is at the very top of Europe according to this indicator, too, is another reason for concern.

***

It should be noted that all of the main negotiation points with the IMF are defensive in some way. This does not mean that they are undesirable, on the contrary. Budget deficit, liquidation of the remaining part of the state-owned sector, dismissal of surplus employees in the public sector and non-performing loans are indeed issues of importance for the Serbian economy. They are used to lower state costs and curb the overheated public expenditure. Removing or diminishing those problems would indirectly improve the business environment and lower costs. Still, one should not harbor any illusions about those measures directly improving the business environment. The IMF does not deal with such issues. If one wishes to improve the business environment in matters which directly incite private investment, then it is up to the Government, not the IMF. Hence, if you are very drunk, the IMF will suggest you to drink less, but it will not deal with what you need to do when you are sober in order to be successful. That should be someone else’s job. Unfortunately, there are no indications of such ideas in the Government.

Economic stagnation

Serbia’s key problem is certainly its stagnant economy. This was not visible immediately after the political shift of 2000, as it was followed by several years of prosperity, the average growth rate in the 2001-2008 period being around 3.5%. A vast majority of economists and politicians have never realized that this growth was not primarily the result of reforms, i.e. good changes in the rules of the game (institutions), but was mainly due to other circumstances. Firstly, the country had just put the wars behind it and such transition from war to peacetime economy and policy always brings growth. Secondly, a period of strong economic prosperity was ongoing worldwide at the time, influencing Serbia, as well. Thirdly, some reforms were undertaken (banking sector, privatization of enterprises, liquidation of some loss-producers), all contributing to growth. Fourthly, following the political changes of 2000, western creditors within the Paris and London club, respectively, have written off large amounts of Serbia’s debt; due to that, public debt has dropped from €14.2 billion or around 220% of the GDP in 2000, to €9.7 billion or 55.5% of the GDP in 2004.

The economic dynamics was reversed due to the 2009 world economic crisis and its influence on Serbia. Like dilapidated boats that perish first during sea storms, Serbia, too, was among the countries whose economies were more severely hit by the crisis. To be truthful, in the period between 2009 and 2015 Serbia did not lose a quarter of its income like Greece did, or even 15pp as Italy or 14pp as Croatia. Still, during this entire period, Serbia has been stagnant and the cumulative sum of the growth rates in 2009-2015 was -0,6 pp, which accounts for less than -0.1pp annually, on average. One could argue that Serbia belongs to second, rather than to the first group of European countries most severely affected by the crisis. Thus, the 2015 income was even lower than it was in 2008.

Table 1: Macroeconomic indicators of Serbia

Source: Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Serbia, various publications. GDP in billions of €; GDP growth, inflation and unemployment expressed in per cent; Current account, public debt and deficit as percent of GDP; Unemployed in millions. Data for 2016 are projections or data concerning the January-April period.

After seven “lost years”, Serbia’s economy has marked its first growth in 2015. The 2015 growth trend has continued and accelerated in 2016 – on an annual level, it is projected at around 2.5% – which is an improvement compared with the previous couple of years, however still insufficient to change the basic impression of a stagnant economy. The key consequence of a stagnant economy at a low development level is the prolonged poverty.

Risk of debt crisis

The second main economic problem of Serbia is the risk of debt crisis and potential bankruptcy of the country. This risk has existed for years, but if bankruptcy would indeed occur, it would automatically become the county’s first economic problem. What are the indicators of an existing risk of debt crisis and – which is even worse – its escalation? There are several undisputed facts which attest to that.

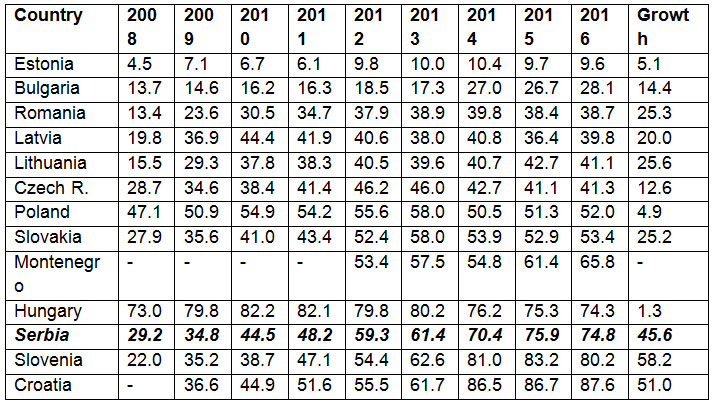

Table 2: Public debt in Eastern European countries

Source: Eurostat; Ministry of Finance of RS. “Growth” in percentage points from 2008 to 2016.

Firstly, Serbia has a high public debt level. Out of thirteen Eastern European countries (Table 2), Serbia is among three countries with the highest public debt which in late 2015 amounted up to 75.9% of the GDP. The Fiscal Council expects the public debt to reach €26 billion or 78% of the GDP by the end of 2016.3 Only two countries out of the 13 that are displayed here have a debt level higher than Serbia – Slovenia and Croatia.

Secondly, Serbia’s debt is increasing rapidly; from 2008 until 2016 it has risen by 45,6pp which, again, is the third-fastest growth among the 13 countries, after Croatia and Slovenia. As EU members – Slovenia also being member of the eurozone – these two countries perhaps may count on the Union’s assistance in case of major difficulties, as was the case with Greece, Portugal and others, whereas Serbia most certainly cannot.

Thirdly, the mechanism of indebtedness is also deserving of a comment. Serbia mainly takes on short-term debt, debt securities being termed between several months and two years.4 This kind of borrowing is more costly than long-term indebtedness. If the two-year euro-denominated debt security yield is 1.18% annually, this would amount to 11.8% over a ten-year period. Thereby, Serbia’s ten-year euro debt securities have varied in financial markets in recent months between 5.8% and 7%, which is less expensive than 11.8%. Dinar-denominated debt securities have been ranging around the 4-5% mark in recent months, which will be further elaborated.

Fourthly, what currently protects Serbia, as well as some other countries, from debt crisis is not something that depends on her. It is a purely external circumstance, namely the fact that benchmark interest rates and cost of capital in the world market are at a historic low. The key benchmark interest rates in zones of responsibility of the FED (Federal Reserve System, USA), ECB (European Central Bank) or the Bank of Japan are hovering around zero. In such conditions, German debt securities offer a yield of around 0.2% (in recent weeks even below zero), Spanish and Italian ones around 1.4% (these are ten-year securities), whereas Serbian yield 6-7%. It is not difficult to imagine what would happen when benchmark interest rates start to grow and once they eventually normalize at 3-5%. Some countries will face debt crisis as a result and the aforementioned figures have shown that Serbia is among the top candidates in Europe for this unfortunate status.

The media have also been covering the currency structure of Serbia’s debt. The euro-denominated debt makes up almost half of Serbia’s public debt, the dollar accounts for around one quarter, the dinar for around one fifth and the rest combined makes up around 5%. There have been objections concerning the high share of the US dollar in the debt. Allegedly, once the dollar rate increases, so does our debt. Although this is true, the objection concerning debt structure is not a valid one. If one would know in advance how the exchange rates will fluctuate in the future, it would be easy to reach a decision on the type of currency for taking on debt. As this is not known, it is impossible to state the currency in which one is supposed to borrow. In order to decrease the exchange rate risk, the share of the two main currencies (dollar, euro) should be balanced in the debt structure. This is the only way of minimizing the risk of exchange rate fluctuations.

As for the dinar-denominated indebtedness, it is considerable, but far from a situation in which there can be talk of a rising dinarization. Dinar-denominated debt securities with a share of close to 20% have a much greater share in the currency structure of debt securities than the dinar has in the total savings – it amounts to only 4%. The high share of dinar debt securities is the result of high yields (interest rates). Of course, a high share of the dinar, of around 20% (which, viewed in absolute figures, amounts to around €5 billion) also implies increased risk for the dinar. If players at financial markets are not satisfied with the yield of dinar debt securities, they will (gradually or abruptly) retreat from them; they will exchange the received dinars for euros, and relocate the euros abroad. This could very likely cause a major drop of the dinar and thus disrupt macroeconomic stability and cause a major disturbance in the country. National Bank of Serbia (NBS) is conducting a risky policy by using high interest rates to motivate banks to purchase dinar-denominated debt securities, piling up a potential avalanche of dinars in debt securities to the amount of around €5 billion. It is now forced to implement a policy of high interest rates, thus being hostage of the banks as it lacks sufficient foreign exchange reserves in order to buy up dinars and use gradual decrease of interest rates as a tool for considerable lessening of the dinar-denominated debt.

Dinarization cannot be carried out by means of a high share of dinar securities in the debt structure. A true indicator of dinarization is the share of the dinar in the total savings and the acceptance of the dinar in market transactions. As the latter issue is influenced by the NBS’s monopoly over money supply, which cannot be affected by the actors in the market, the dinar-denominated savings remain as the only true indicator of dinarization. That is because it is only that operation in which players pick a currency themselves. A very low level of dinar savings is a result of the domestic currency’s instability in the previous decades and years, urging savings account owners to seek other options. For the sake of comparison, from 1913 to this day the US dollar has undergone an inflation of around 2,300%, whereas the dinar’s has been around 6,700% from January 21 1994 (i.e. the introduction of the so-called Avram’s5 dinar) until now. This would mean that the dinar is up to 15 times more prone to inflation in comparison with the dollar during the observed periods. It takes decades of monetary stability to increase trust in the dinar and thus the share of the dinar-denominated savings. Therefore, one should not expect a soon occurrence of a higher level of dinarization. Due to the bad dinar, Serbia is forced to rely on the euro as its main currency. This affects the monetary policy in Serbia which is extremely limited. In other words, it means that it is basically determined by the situation in the world market.

Sustainability of the Arrangement with the IMF

Regardless of the improved budgetary balance, the IMF will request for other conditions of the arrangement to be fulfilled, primarily those with regard to privatization of state-owned enterprises and dismissal of surplus employees in the public sector. Both those questions are very sensitive for the Government which is why one can be generally doubtful as to whether the Government will indeed implement everything that was agreed upon. It is more likely that the promises will be fulfilled only partially. The Government is probably counting on a certain level of lenience by the IMF. This was also indicated by a statement made by James Roaf before the onset of negotiations on the fourth and fifth review. When asked “What is the line that the IMF will not cross in terms of promises that Serbia made to the IMF?“, Roaf said: “This is not the best way to think of our relationship. The IMF is using its technical know-how and experience to support Serbia’s own economic reform program. The program is a living document, which can change as economic circumstances and political priorities change.”6 So, the IMF’s attitude lacks principles and harshness, but the question remains whether one can count on sufficient lenience as a result. As the continuation of the program is in the both parties’ (IMF, Government) interest, this is the likely scenario. The fact that it will have to implement at least part of what was promised will be painful enough for the Serbian Government. This will most likely not be satisfactory for the IMF but it will make its positive assessment of the arrangement’s development possible. It is still at the first half of the road (out of a total of 12 reviews) which provides the IMF with enough opportunities to temporarily halt the arrangement or even abandon it, if necessity should arise. Let us remind of the fact that the previous arrangement with the IMF was abandoned by the Serbian Government in 2012 due to the upcoming elections and the Government’s unwillingness to tie its hands in the area of state expenditure on that occasion.

Finally, we should note that the visit by the IMF to Serbia that took place June 9-21 was a highly untypical one. Firstly, it was used to merge the fourth and fifth, out of a total of 12 reviews of the stand-by arrangement. Both series of talks were held with the caretaker government: in April when elections had already been called, and in June after the elections took place but a new government was yet to be formed. Secondly, the negotiations were led, on the IMF’s side, by James Roaf, head of the IMF Mission in Serbia, rather than someone from the IMF headquarters in Washington. Thirdly, very little details have been publicized during the negotiations on their contents. Fourthly, the overall assessment by the IMF at the end of the negotiations on the extent to which Serbia fulfills the conditions of the existing arrangement was uncharacteristically positive7 both as a whole, as well as in all important elements of the agreement viewed individually. It remains to be seen in further reviews whether such assessments by the IMF have been well-founded. By the way, the fourth and fifth review will be subject of verification by both the IMF Board of Directors, as well as the Government of Serbia.

Deterioration of relations with the West

In mid-June 2016 news have quickly spread in the media of the Prime Minister of Serbia postponing his visits to Brussels and Washington. Many were surprised by this, in light of support received by Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic from western capitals in recent years. This support had assumed distasteful proportions, bearing in mind policies led by Vucic in the country, which were reduced to strengthening personal power, demolition of institutions, media control, violation of rights and repression against the opposition and other opponents. All of this was known in western capitals but still, they did not stop supporting the Prime Minister.

What changed so suddenly then, urging the Prime Minister to postpone the visit? It is probably due to a chain of multiple events.

Firstly, even though Prime Minister Vucic did display cooperativeness in resolving the status of Kosovo, which is at the top of western countries’ agenda when it comes to the Balkans, the initial positive dynamics has fizzled out and little has been accomplished.

Secondly, leading western countries have long been dissatisfied with Serbia’s foreign political and economic inclination towards Russia and China. In terms of energy supply, Serbia is highly dependent on Russia, and when it comes to natural gas there is a 100% dependency, whereas the oil product market is dominated by Russian companies (Gazprom and Lukoil hold around 60% of the market). Apart from the Russian emergency intervention base in Nis, there is now talk of a new Russian military base at the Zrenjanin airport. Also, Serbia’s avoidance to introduce sanctions to Russia is being increasingly frowned upon by the West. Chinese investments in infrastructural projects in Serbia and the sale of the Smederevo Steelworks to Chinese state-owned giant HBIS (along with the unresolved issue of production scope and placement in the EU market) are obvious signs of a stronger Chinese presence in Serbia. Finally, smear campaigns against certain western politicians in Serbian pro-regime media are certainly one of the reasons for pressuring the Serbian Prime Minister in order for that shameful campaign to be halted. Add to this the probable political pressures surrounding the formation of the Serbian Government (which are difficult to align with similar pressures from Russia) and it is also possible that there are additional reasons, as well, that have not been publicized.

Obviously, problematic cases have multiplied and we have suddenly learned that the idyllic relation between the West and Serbia has ceased to exist. Of course, the problems could be resolved and the idyllic relations may return. This seems more probable. Still, the problems could increase, leading to a rerun of events from the Slobodan Milosevic era, albeit in a new version. Milosevic, too, was first hailed by the West as the “factor of peace and stability“, only to gradually become a culprit and eventually the main culprit for all regional confrontations and problems. Due to such policies, Serbia has embarked on a confrontation with the West which ended in defeat following the NATO military intervention. As the defeated side, Serbia became more cooperative when faced with the West’s demands, but it has not become a part of the West. On the contrary, she stubbornly kept on relying on Russia (and China), refusing the very notion of joining NATO, being declaratively in favor of joining the EU but failing to do any serious work in order to improve its institutions and adjust its policies to that goal, fostering silent nationalism, etc.

Even though the primary responsibility lies upon Serbia, the West may have added to this deterioration of relations. The Balkans has long exited the focus of USA and NATO, respectively. Conflicts ranging from the Ukraine to Libya and Iraq have occupied the attention of the USA, NATO and the EU. The EU has temporarily suspended its enlargement and given the current situation in the Union, it is doubtful that there will even be one in the future. That way, the main “carrot” for Serbia and a few other Balkan countries which are still outside the Union has diminished, if not disappeared completely.

This decrease of western influence in the region has basically represented an open call to others to strengthen their own. Along with historical and other traditional reasons, there is also an emergence of Serbia’s economic, military and foreign-political projects with Russia and China. Clearly, the West has made an assessment that Serbia’s slide towards the East needs to be stopped, while increasing the pressure to deliver what was promised or signed by Serbian top authorities (concerning Kosovo, Bosnia, etc).

Epilogue

Serbia faces two paths. One is further deterioration of relations with the West, which would lead to additional worsening of the country’s foreign-political position and deepening of economic and social difficulties in the country. This path would rather quickly lead to termination of the arrangement with the IMF, weakening of the country’s credit rating, difficulties in debt servicing which would turn into a debt default. It would lead to a drop in economic activity, to the necessity of further decrease in state expenditure, rise of inflation and expected commodity shortages. There is no need to emphasize how negatively this would influence Serbia’s citizens’ living circumstances, as the memory of the Milosevic era is still fresh. The fact that the path to a conflict with the West and its price is familiar gives reason for hope that the current deterioration of relations with western capitals will soon become just an episode and that good relations will continue.

Serbia’s problems are not going to disappear because of those good relations, but they will be somewhat smaller than otherwise. The economy will remain stagnant until more resolute market-oriented reforms are carried out and rule of law is promoted; debt growth will increase the risk of entering a debt crisis and each review of the arrangement with the IMF will be accompanied with uncertainty regarding its ultimate fate. The IMF mission has left Serbia, but the problems remain.

The author is professor of economics from Belgrade.

Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 06.07.2016.

Peščanik.net, 09.07.2016.

________________

- According to a statement by Minister of Finance Dusan Vujovic, dated June 11 2016, the deficit during the first five months of 2016 amounts to 11 billion dinars, whereas the planned deficit had been around 60 billion. There are no further details in connection with these figures.

- On June 20 2016, Beta news agency broadcast a report under the headline “14.500 People Have Left the State Administration“. http://beta.rs/ekonomija/ekonomija-srbija/34890-iz-drzavne-uprave-otislo-14-500-ljudi

- Cf. Fiscal Council (2016) Fiscal Developments in 2016, Consolidation and Reforms 2016-2020, Belgrade: FS, p. 1-72, here p. 3. http://www.fiskalnisavet.rs/doc/ocene-i-misljenja/2016/Fiskalna_kretanja_2016_fiskalna_konsolidacija_2016-2020.pdf

- Cf. http://www.mfin.gov.rs/pages/issue.php?id=7139

- Avram is the nickname of NBS Governor Dragoslav Avramovic (1919-2001).

- “No wage increase. Not this year and maybe not next.” Interview with James Roaf, NIN weekly, No. 3415, June 9 2016, p. 32.

- Not only in Serbian media, but also in a Reuters commentary dated June 21 2016, entitled “IMF commends Serbia’s economic policies, urges more effort on debt” http://www.brecorder.com/world/global-business-a-economy/304904-imf-commends-serbias-economic-policies-urges-more-effort-on-debt.html