Why is World War One so important? Why does it cause such strong emotions? Why is it politically abused?

Let’s start with the important fact that it was a historian who said that the First World War is a key point of Serbian identity. A historian mustn’t say something like this. The one thing that is certain about these analyses of identity construction is that they emerge based on stereotypes, various emotional adaptations of history. A historian should be interested in what was life like in Serbian villages during those six years when men were away at war, from 1912 to 1918, how severe was the famine, how many children died? When a historian says that these things constitute the identity, it means that he is saying that historians should despise reality and deal, foremost, with emotions that we can squeeze out of the past.

The key moment happened in 1972, when four-volume novel “Time of death” by Dobrica Cosic was published. Basically, the novel determined historic remembrance of World War One, but important thing to remember is that 1972 was Dobrica Cosic’s political charge, i.e. that it was too soon. Yugoslavia was not yet in crisis that was to happen in the eighties, and that novel didn’t immediately play the role it would later play, but a role of, to put it metaphorically, ideological sinking river. Another 10 years had to pass and everything that happened from 1980s onward had to happen, i.e. Tito’s death, Kosovo crisis that started in 1981 and, of course, deep economic crisis of Yugoslavia. These three and who knows what other triggers questioned Yugoslav federation and posed a question of its reorganization or its destruction in the early eighties.

That was the political context needed for World War One to get its proper mythical place, and that mythical place was set in 1983, when a play based on Dobrica Cosic’s novel “Kolubara battle” was staged in Jugoslovensko dramsko theatre. I think that was a decisive moment. The newspapers wrote that the play initiated, as they called it, an avalanche of history, that people entered the theatre as if coming into a church. All of us who saw the play remember the audience standing, cheering, shouting “attack”, crying, laughing; it was indeed a religious ritual we could compare with initiation into a new-born nation, and I think that that play was the real trigger. However, of course, it couldn’t create homogenization of the nation that was needed; not entire Serbia could come to Jugoslovensko dramsko.

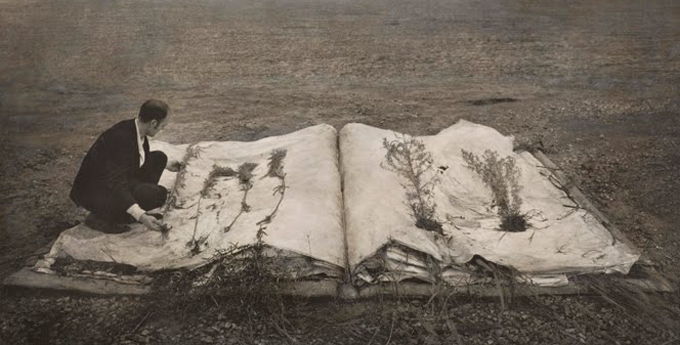

It was something else that pushed the entire Serbia and again it came from the culture; now we are in the year 1985, when a novel “Book of Milutin” by Danko Popovic was published. That was a decisive event, and I think that we can call that text “a little red book”, remembering Mao Tze Tung’s Cultural Revolution. That book played the key role. With some 140 pages, it was a digest of Dobrica Cosic’s novel. All of the ideas were there. The important thing to mention here, the thing that makes it clear that this was no cultural, let alone historical phenomenon, but completely new political situation, is the fact that 18 editions of that book were published during a year and a half and that it is considered that 500,000 copies were sold. That was a book that reached every Serbian household and conveyed main mythical ideas.

Just a reminder, Milutin is a Serbian peasant and the book starts with his participation in Balkan wars and ends with his death in so-called communist prisons. So, he goes through the entire 20th century and is a personification of Serbian nation. It was said that he is an arch-type of a Serbian peasant, that he is a sum of national truths, that he is a bearer of Serbian historical faith, a collective hero, and I think that it was best put by the writer himself, Danko Popovic, when he said that Milutin is the grandfather of all Serbs. That book was considered an ideological pamphlet. It conveyed Dobrica Cosic’s ideas to the masses.

First World War didn’t return to focus until 2013, when preparations for the centennial began and, of course, Pescanik immediately reacted. We asked ourselves what exactly was this about and now I think that we have all pieces of the puzzle. In order to understand how it is possible that World War One always causes such heat, we have to analyze those key mythical points, to see what are the bases of, like that historian said, Serbian identity, i.e. that mythical and emotional understanding of the history.

World War One is extremely important because several battles that happened during it, starting with the battles of Cer and Kolubara to the break-through of Thessaloniki front, are of key importance for development of the myth about warrior and victorious nation. I think that Arsenije Jovanovic, who staged “Kolubara battle” in theater, defined it best in an interview when he said that Kolubara battle is actually Kosovo battle, but with a victory at the end. That doesn’t mean that victory is more important than the defeat. On the contrary, the defeat is more important, but nevertheless a story about victory feels good, it is important for the national self-esteem, for heroization of the nation.

By comparing literature and history text books, my goal is to prove that these works of literature, from Dobrica Cosic to “Book of Milutin” entered our system of education directly, completely skipping critical historiography. Literature entered our system of education directly.

The idea of heroization of the past enters today’s school books, for example, by quoting a French officer who had said – let’s believe that he had really said that – “Only French cavalry, but with great effort, could keep up with Serbian infantry”. In a romantic memory of a French officer something like this is completely acceptable, but the fact that it entered a history textbook, without any deflection, without questioning how is it possible that the French cavalry struggles to keep up with Serbian infantry on the altitudes of Kajmakcalan, shows clearly that this is about assigning supernatural attributes to Serbian army and Serbian people. Let me remind you, at the end of the eighties, during the preparations for the war, it was said that “all our wars were victorious, our enemies lost all wars” – and it fed national arrogance. However, it turns out that when you base something on a myth, the deal usually turns upside down, and Serbia suffered all those great defeats in the nineties.

The second key idea that makes World War One a founding myth is an idea of a victim-nation, that self-victimization is especially easily transcribed to World War One when Serbia indeed lost between one third and one fourth of its population. But, the question of actual number of victims and the question of our attitudes towards these victims and the way we remember them are two completely separate issues. Anyway, that self-victimization, which means abuse of those victims, is extremely important because victim-nation has all those moral and political privileges, its every action is forgiven in advance and used to constantly remind all neighboring nations of that never-paid debt. Or, as Amos Oz said “we are witnesses of a world championship for the biggest victim of all nations”. I think that Serbs have entered this competition a long time ago.

Unfortunately, this also entered the history education and the sources are often used here. It is a typical mechanism, when you say “there, the sources say so”. The question, of course, is about your attitude towards the source, how will you guide a student to read that source or whether it is up to a 13 year old student alone to understand the source. For example, there is a description of war time situation in town of Valjevo in the current textbook. It says that occupying forces reported that “both men and women await death sentence stoically, with ease. The death penalty has lost all effectiveness. No one was afraid to die”. And when we look at any description in today’s textbooks we see that it is not only an idea, but the very language of Dobrica Cosic, so the textbooks say that “Serbia was the land of death”. Again, it is promotion of those epic values that nurture despise of death and prepare new generations for the idea that death is the climax they strive to experience.

New mythical point that can be built upon the events of World War One is the idea of Serbian people as generous, the one that does everything for others, and there we come to an important point of the whole ideology – the feeling of injustice, because it is probably the strongest glue of a nation. It is the one that homogenizes all individuals with a strong sense that we are object of constant historic injustice – you keep giving, but you are always misunderstood and, eventually, end up worst. It is important because it homogenizes the nation but also because it is the easiest trigger for a rematch. This is the syndrome of unrequited love that actually mobilizes you, which was, if you remember the late eighties and early nineties, the key to start the war and the destruction of Yugoslavia. Milutin constantly speaks about it. He keeps saying “we’re going to free others, we are dying for others,” and then counts what we do for the Slovenians, for the Croats, and so on, but he always has the feeling that his victim is denied, that nobody wants it, that everyone looks at him weird.

Of course, it is just literature and we can talk about “Book of Milutin” in different ways but, as some would say, literature has the right to be wrong. Textbooks don’t have the right to be wrong, they bear the signature of the Ministry of Education, and now we will see how these Milutin’s thoughts went directly into the textbook, skipping the results of scientific historiography – primarily idea that Serbia liberated other Yugoslav nations and gave them their states. Another extremely important component of the Serbian nationalism is that each time Serbia lent a hand to nations who always found themselves at the wrong side of history. But we, out of our generosity, always lend them a hand and help them cross to the right side, guide them through the moral notch of history, but still they abuse our effort again and again. This is a quotation from the textbook: “Serbia has enabled other Yugoslav nations to leave the defeated side and join the winners, by forming the Yugoslav state.”

The next mythical item that was extremely important in the eighties, but lost nothing if its emotional potential since, is the myth of an enemy, which can also be built on the basis of interpretation of World War One, especially when we talk about all neighboring nations, but also when we talk about Europe as such. Because, Austria-Hungary and Germany against whom we were at war are not our only enemies, but, by God, allies who have tried on several occasions to negotiate with our enemies, the Italians and the Bulgarians, who wanted to give our territory, and so on, they are all also our enemies. Facts may be such, but again the question is what you will conclude from this. Do you conclude that when dealing with the great powers you should watch over your interests in any given situation, or are you supposed to turn them all into your enemies again, which is the case with our literature and our education system. Why is the enemy myth important? It is an additional point that helps vengeance. And if anyone was unclear about that, Milutin would conclude, and I quote: “We need to pay them back, to kill the Arnauts. They killed ours, smashed their heads with ax loops.” He directly calls for revenge. And every time we line up the enemies like this, we need to know that it is always a call for a rematch.

Finally we come to the last myth. It is a myth of Yugoslavia, which was again heavily influenced by First World War because of course that’s when the state was created. Here we come to key points of both Dobrica Cosic and Milutin, and today’s textbooks, and today’s political response to First World War, because everything mentioned above – the heroism, great Serbian victims, big misunderstanding and severe injustice – that was all in vain. In words of Dobrica Cosic: Yugoslavia was a historical mistake. This idea is completely openly found in, for example, the eighth grade textbook. Today’s textbook says: “Serbia left the acceptable Piedmont of Serbhood” – using the term acceptable textbook writer joins debate and says what is right or wrong – “Serbia left the acceptable Piedmont of Serbhood and proclaimed itself the foggy Piedmont of Yugoslavhood. “ Again, the use of adjectives is clearly suggestive. “It was a hasty and poorly thought-out reversal, the fatal myth of Yugoslav state.” There is no need to stress that textbooks are certainly not the place for this kind of debate nor for blaming historical heroes, historical ideas and situations – but, of course, since our education has no educational purpose, these things are the key.

I have briefly shown key mythical points, and now we can move on to the political sphere today. The state responded with a conference in the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, opened by the president who filed another report on World War One, and again, with the same emotional charge, he said that “Serbia will not allow revisionism, Serbia will counter, this time Serbia will not be silent”, and so on. He still lives in that tension. However, it is important that soon after, or even at the same time this conference at the Academy of Sciences and Arts took place, Milorad Dodik and Emir Kusturica came to visit, and on this occasion both the President Tomislav Nikolic and PM Aleksandar Vucic said that they would not go to Sarajevo, but to Andricgrad instead where they would mark the assassination that took place in Sarajevo by themselves.

By this gesture they clearly wanted to show that Serbia does not even want to pretend that is a different Serbia today. Those who keep saying that this is now some major political shift, actually showed by this gesture that not only did they not bring about anything new but that they symbolically want to tell everyone that this has always been and always is that same Serbia which will not offer peace, which will not take this opportunity to just go to Sarajevo. They go to Kusturica in Andricgrad. They say exactly what we can deduce from the rhetoric of Tomislav Nikolic that the war never ended, that we’re still at war of the nineties, which is clearly stated by going to Republika Srpska. What’s even worse, it shows that we are still in 1914 and that the war is still on.

From the radio show 27 June 2014

Translated by Marijana Simic

Peščanik.net, 05.07.2014.

- Biografija

- Latest Posts

Latest posts by Dubravka Stojanović (see all)

- Posthumni život Ustava iz 1974. - 23/02/2024

- Prošlost dolazi - 30/11/2023

- Prošlost dolazi, 2. deo - 24/11/2023